Ready to transform your program or farm?

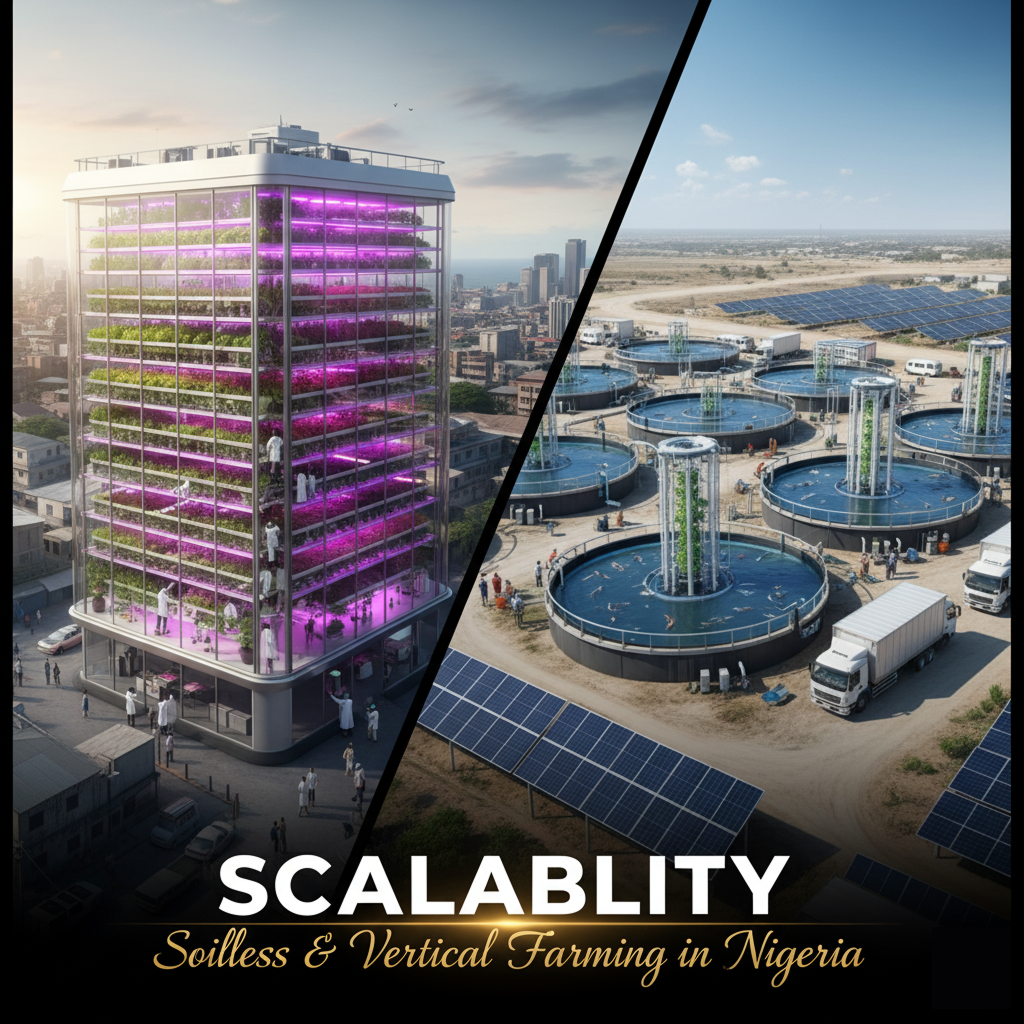

The promise of soilless and vertical farming is undeniably alluring. In a world grappling with climate change, shrinking arable land, and growing populations, these technologies present a vision of a hyper-efficient agricultural future: climate-resilient, high-yield, and close to urban centers. For Africa, a continent on the frontline of these challenges, the appeal is even stronger. However, a transition from promising potential to scalable reality is fraught with significant structural, economic, and infrastructural hurdles. While the technology is sound, its widespread applicability within the current African context is highly questionable.

The single greatest barrier to the adoption of soilless and vertical farming in Africa is the prohibitive cost. The core components of these systems from hydroponic gullies and LED grow lights to automated fertigation systems and climate-control technology are overwhelmingly imported. This subjects the initial capital expenditure to foreign exchange volatility, instantly placing it beyond the reach of the vast majority of the continent’s farmers.

Furthermore, the operational inputs are specialized. Nutrient solutions, high-quality seeds optimized for controlled environments, and specific growing media like coco coir or rockwool are often not locally produced, necessitating continuous importation. This creates a dependency on international supply chains and adds a layer of cost and complexity that traditional farming does not have. The economic model simply does not align with the reality of Africa’s agricultural backbone: smallholder farmers who operate with limited capital and are highly risk-averse. Expecting a subsistence farmer to invest in a system that costs multiples of their annual income is not a viable strategy for scale.

A critical, often overlooked, limitation is the narrow range of crops that are currently economically viable in most vertical farming systems. These systems excel at producing high-value, fast-growing, low-calorie crops like leafy greens (lettuce, kale), herbs (basil, mint), and microgreens. While these products have a place in niche urban and hospitality markets, they do not address the foundational dietary needs of the majority of the African population.

The continent’s food security is built on staple crops like maize, cassava, yams, rice, and legumes. These are calorie-dense crops that are not technically or economically suited for vertical farming. The energy and space requirements to produce a kilogram of cassava in a vertical farm, for instance, would be astronomically high. Therefore, while soilless farming can supplement food supply, it cannot be positioned as a replacement for traditional agriculture in ensuring staple food security.

This crop mismatch leads directly to a market problem. The primary outlets for agricultural produce in Africa are informal, open-air markets. These channels are characterized by price sensitivity and a focus on staple goods. A farmer with a premium-priced head of hydroponic lettuce will struggle to find consistent offtake in a market where consumers are focused on affordability and dietary staples. The structured, large-scale retail chains and hospitality industries that could absorb these premium products represent only a fraction of the overall food market, limiting the potential for broad-scale impact.

Even if a farmer overcomes the cost and crop hurdles, they are immediately confronted by the continent’s infrastructural challenges. Vertical farms are energy-intensive, relying on a stable and affordable supply of electricity to power lights and climate control systems. In many African countries, the power grid is unreliable and expensive, forcing operators to invest in costly backup generators, which further inflates operational costs.

Moreover, inadequate infrastructure like poor road networks and inefficient logistics makes reaching the few available premium markets difficult. The competitive advantage of urban-based vertical farming is diminished if produce cannot be moved efficiently, leading to spoilage and increased transportation costs. These logistical bottlenecks erode already thin margins and make the high initial investment even more difficult to justify.

Despite these significant challenges, soilless and vertical farming are not without a place in Africa. The technology finds its most logical and justifiable application in a specific niche: backward integration for large industrial organizations.

Consider a large food processing company that requires a consistent supply of high-quality tomatoes for its paste factory, a beverage company needing specific varieties of mint for its products, or a pharmaceutical firm sourcing medicinal herbs. For such organizations, the investment in a controlled environment agriculture (CEA) system is a strategic decision.

In this context, the high CAPEX is a justifiable business expense to secure a critical input for a larger, profitable enterprise, whether it services local consumer markets or the export market.

To be clear, the argument is not that soilless and vertical farming have no future in Africa. The technology holds immense potential. However, we must be pragmatic and direct our focus where it can be truly effective. The narrative of this technology “solving” food security by empowering smallholder farmers is, for now, a fallacy. The path to scalability lies not in widespread, small-scale adoption, but in strategic, well-capitalized, and vertically integrated industrial applications. As the technology matures, costs decrease, and local manufacturing of inputs and equipment develops, the picture may change. But for the foreseeable future, its role will be that of a high-tech, niche solution for specific industrial needs rather than a silver bullet for the continent’s broader agricultural challenges.