Ready to transform your program or farm?

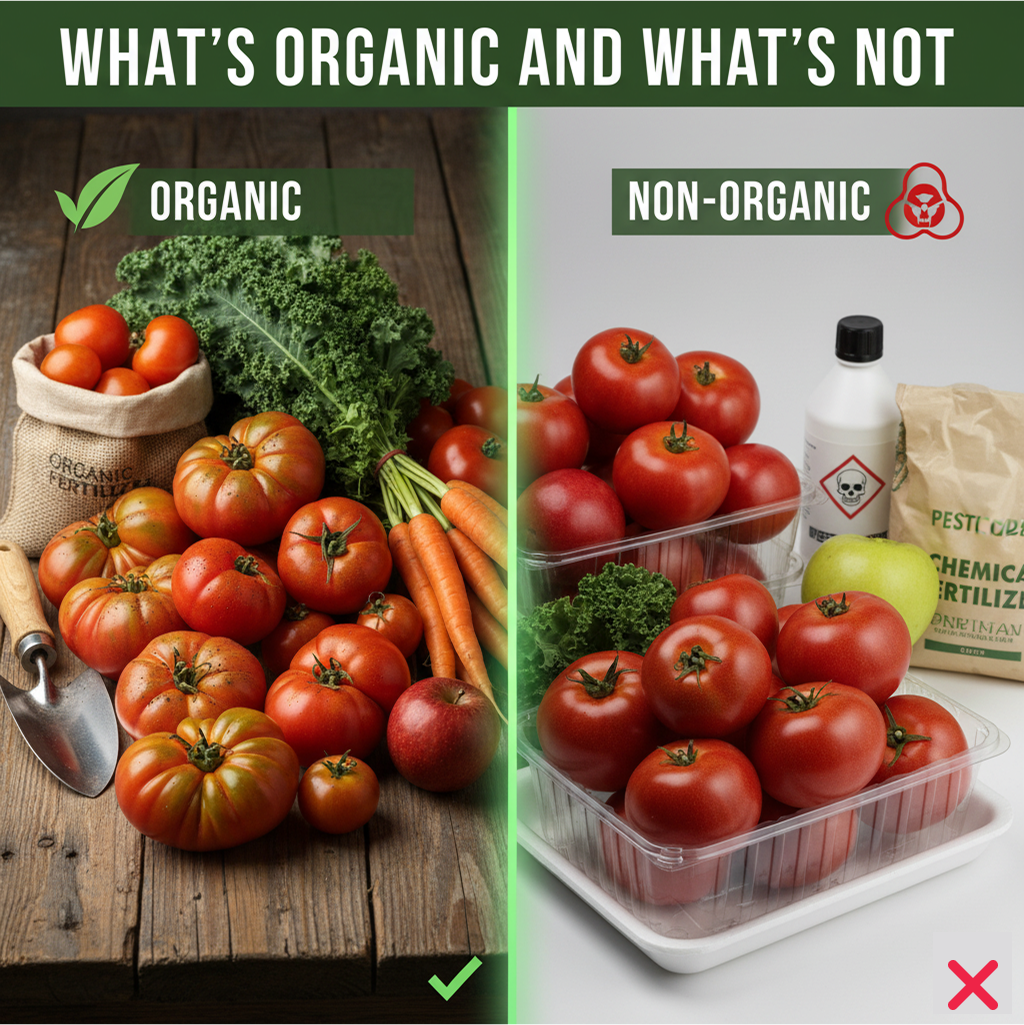

We’d think “organic” is a simple term. It should mean food grown naturally, without harmful chemicals, in a way that’s good for the earth. But the moment you look closer, this simple idea shatters into a thousand bureaucratic pieces. The “organic” label today often has less to do with the final product’s safety and quality and more to do with a rigid, soil-centric philosophy that is struggling to keep pace with modern agricultural science.

This poses a huge dilemma for innovative farming methods like hydroponics, which can produce food that is clean, safe, and highly nutritious, yet is often locked out of the “organic” club.

The confusion you highlighted in the United States has evolved, but it hasn’t disappeared. The USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) did create a federal standard, replacing the chaotic patchwork of state and private rules. However, it also sparked a fierce, ongoing debate: can a plant grown without soil be organic? After years of lawsuits and deliberation, the USDA has controversially allowed some hydroponic operations to be certified, but the decision remains deeply contested by soil-purist organic groups.

If you look across the Atlantic, the picture is different. The European Union has taken a much harder line. Their organic regulations are explicitly tied to cultivation in soil. The philosophy is that organic practice is inseparable from nurturing soil life and ecology. For the EU, the answer is a firm “no”—hydroponics cannot be organic. This creates a major trade and philosophical divide, where a product’s “organic” status literally changes as it crosses the ocean.

Here in Africa, the situation is even more complex. There is no single, continent-wide standard. Farmers and nations often find themselves navigating multiple systems:

This forces an African farmer to choose: do I follow a standard for my local market, or do I adopt a rigid foreign standard to access the export market?

The heart of the issue lies in a clash between a philosophy of “naturalness” and the scientific reality of what makes food safe and nutritious.

Organic rules often prohibit the use of pure, refined mineral salts—the very foundation of a precise hydroponic nutrient solution. Instead, they mandate unrefined, mined minerals. As you correctly pointed out, this is a classic example of the naturalistic fallacy, the flawed assumption that “natural” is always safer.

Refining these minerals removes such impurities, creating a purer, safer product. Yet, in the world of organic bureaucracy, this act of purification renders them “synthetic” and therefore forbidden. Meanwhile, hydroponics uses food-grade, refined nutrients to provide plants exactly what they need, with no unwanted contaminants.

A primary driver for consumers choosing organic is the avoidance of pesticides. However, the organic reliance on animal manures introduces a significant biological hazard. As your text noted, outbreaks of Salmonella and E. coli have been traced back to crops contaminated by manure used as fertilizer.

In stark contrast, a well-run hydroponic system is a controlled environment. It operates without soil-borne diseases and often without the need for any pesticides. The risk of pathogen contamination from manure is completely eliminated. Which is truly “safer”? The food grown in potentially pathogen-carrying soil, or the food grown in a clean, sterile, soilless medium?

A historical criticism of hydroponics was its environmental footprint, particularly the disposal of single-use media like rockwool. However, the industry has evolved dramatically.

Today’s advanced hydroponic systems are models of sustainability:

The argument that hydroponics is inherently unsustainable is simply outdated.

The “organic” label is trapped in a 20th-century definition. It prioritizes a method (cultivation in soil) over the outcome (safe, nutritious, sustainably grown food).

Perhaps it’s time to look beyond a single, flawed label. Consumers are ultimately seeking trust. They want food that is pesticide-free, nutrient-rich, and grown with minimal impact on the environment. Hydroponics and other soilless methods can deliver on all these promises.

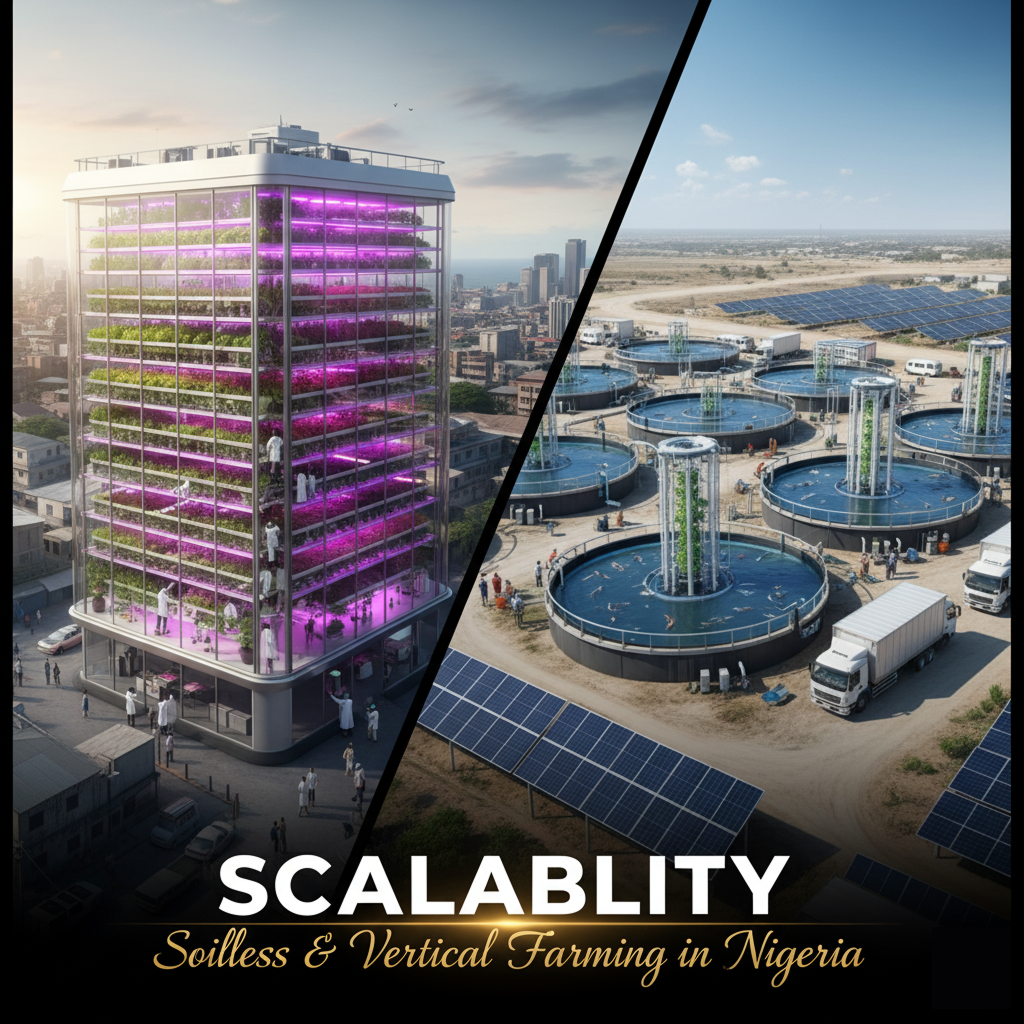

For a continent like Africa, where food security, water conservation, and crop consistency are paramount, clinging to an imported, soil-centric organic ideology seems counterproductive. We need solutions that work for our climate and our people. Advanced soilless farming offers a powerful tool to achieve that.

The conversation needs to shift. Instead of asking “Is it organic?” we should be asking, “Is it safe? Is it sustainable? Is it nutritious?” On those counts, modern hydroponics makes an exceptionally strong case. It’s time for the definition of “good food” to catch up with the reality of how it can be grown.